With the rapid development of digital technology, numerous concepts have proliferated in the virtual world, among which, virtual assets stand out as a prominent one. In practice, while some countries have recognized their legal validity, Vietnam has yet to officially acknowledge virtual assets. It appears as a commonly circulated asset in Vietnam while lacking legal status and specific identification provisions, leading to various loopholes and challenges for transactions and practical enforcement. The circumstance is deemed inappropriate and out of step with global trends as well as the era of digital technology development. Given that, this article will provide an overview of virtual assets under Vietnamese law, thereby offering some recommendations to address the question of whether virtual assets should be officially unlocked for recognition.

Virtual Assets from International Legal Perspective

Definition

Virtual asset is a relatively new concept sporadically being defined worldwide. Whether officially defined in the form of legal regulations or not, the definition of virtual assets still has various interpretations.

For instance, virtual assets defined by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) refer to any digital representation of value (excluding fiat currencies) that can be digitally traded, transferred, or used for payment. As another example, the Financial Services and Markets Regulations (FSMR) define virtual assets as digital representation of value which can be digitally traded and functions as a medium of exchange and/or a unit of account and/or a store of value without having legal tender status in any jurisdiction. Virtual assets are neither issued nor guaranteed by any jurisdiction and fulfill the above functions only by agreement within the community of users of the virtual assets and distinguished from fiat currency and electronic money.

From another approach, we can understand virtual assets through their manifestations. For instance, according to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), virtual assets are a type of asset in cyberspace, referring to a complex environment shaped by the interaction of users, software, and services on the internet through connected technical devices and networks. Besides, we can refer to the definition of the European Central Bank (ECB), identifying virtual assets as digital currency that is not regulated by a central bank, issued, and controlled by the developer, used, and accepted among members of a given virtual community.

In general, virtual assets possess the following characteristics:

- Appearing in the virtual world as a type of asset without issuance or guarantee of any competent authority;

- Using blockchain technology or other type along with encryption technology, to establish and verify transactions transparently, securely, and reliably;

- Serving as means of exchange or assets available for transactions, transfers, or other purposes such as payments or investments, etc.; and

- The owner’s rights over a virtual asset are expressed by their actions that have an impact on the asset. These rights are legally recognized and enforced based on the will of the rights holder when exercising their powers lawfully.

Furthermore, depending on the interpretation, the recognition of virtual assets as traditional assets would be accepted in each country or not. Currently, in a broad term, El Salvador, the Central African Republic (CAR), etc. have acknowledged the legal validity of virtual currency (i.e., Bitcoin).

Distinguishing Virtual Assets and Other Similar Types

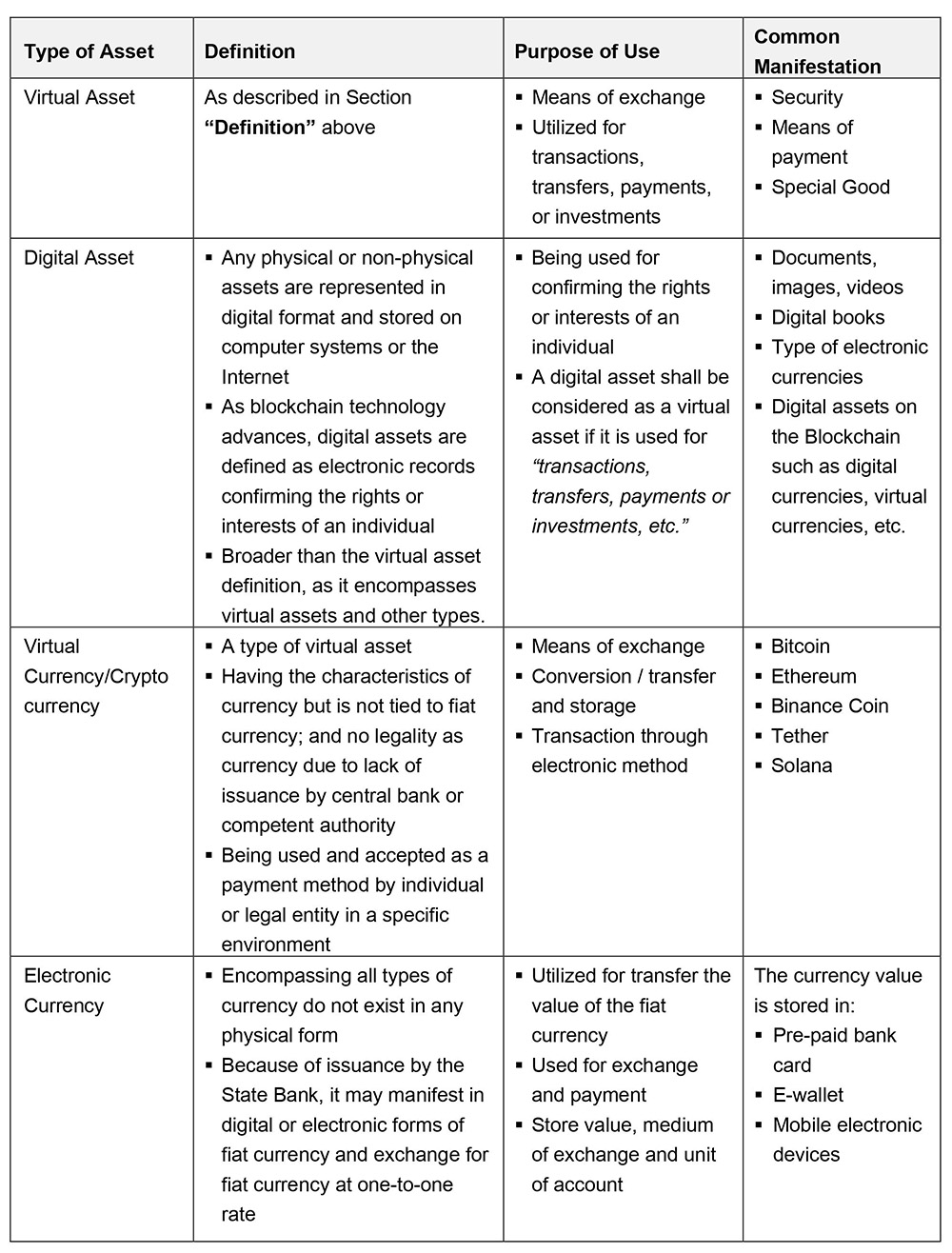

In actuality, “virtual asset” and “digital asset” are occasionally used synonymously. Fundamentally, these concepts are not identical, with digital assets being considered broader. To clarify their nature, the authors will contrast them with other types of cryptocurrencies and digital currencies based on the following precise criteria:

Virtual Assets and Associated Infringements in the World

Delving deeper into this article, world-shaking cases involving virtual assets provide insight into the actual trading of this type of asset.

The first renowned fraud case revolves around the virtual currency celebrity – Do Kwon and his fraudulent activities valued at trillions of USD. The accusations by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission indicate that Do Kwon and his own company repeatedly made inaccurate statements regarding the stability of a stablecoin – TerraUSD by associating it with stable assets, including the U.S. dollar. Moreover, to quickly attract investors, Do Kwon implemented a strategy allowing customers to borrow TerraUSD at an interest rate of up to 20% per year. However, the crucial point is that Do Kwon advocated for decentralized finance while making unilateral decisions, causing the cryptocurrency market to incur over USD40 billion in losses. Subsequently, Do Kwon faced charges in the U.S. for multi-trillion-dollar digital asset fraud and in South Korea for fraud and violating local capital market laws. Currently, Do Kwon’s alleged involvements are pending an official conclusion on his virtual currency fraud.

Most recently, in another development in November 2023, Changpeng Zhao, the former founder and CEO of Binance – the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, pleaded guilty to criminal charges related to money laundering. According to the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), Changpeng Zhao and others were accused of failing to implement effective anti-money laundering and knowingly profiting from the US market without conducting control measures. Moreover, such exchange allowed illegal entities to conduct more than 100,000 transactions related to terrorism and illegal drug activities as well as 1,5 million trading virtual currencies in violation of US sanctions without reporting any suspicious transaction behavior.

Virtual Assets in Vietnamese Law

Overview

Back to the early days of virtual assets and virtual currencies appearing, Bitcoin and other similar virtual currencies were determined to be neither a type of money nor legal means of payment in Vietnam. The issuance, supply, and use of illegal means of payment will be subject to administrative sanctions or criminal prosecution for more serious acts. Additionally, the use of virtual assets and virtual currencies for the purpose of money laundering, tax evasion, etc. is also handled as regulated by Vietnamese law.

Furthermore, it is necessary to affirm that the current Vietnamese legal system does not have specific regulations regarding the recognition of virtual assets as one of the legitimate properties. Accordingly, the Civil Code 2015 stipulates that property comprises “objects, money, valuable papers and property rights”. However, the raising number of legal issues concerning virtual assets has gradually urged policymakers in Vietnam to seek the answer to the question of whether virtual assets are considered property or not.

Accordingly, Vietnam has taken the first actions in the last five years to recognize virtual assets and establish their legal validity. It is proven that several virtual assets management issues have been raised in Report No. 255/BC-BTP dated 29 October 2018 of the Ministry of Justice on comprehensively evaluating virtual assets, virtual currencies in Vietnam and international laws and practices, proposing directions for improvement. During the same period, Directive No. 10/CT-TTg of the Prime Minister, and Directive No. 02/CT-NHNN of the Governor of the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) also have requirements on enhancing management of transactions and activities related to virtual currencies, especially Bitcoin. Alongside this, Decision No. 242/QD-TTg dated 28 January 2019 of the Prime Minister approving the project “Restructuring the stock market and insurance market to 2020 and orientation to 2025”, etc. These are considered important steps in the research process towards building a legal framework for virtual assets in Vietnam.

Types of Virtual Assets Emerging in Vietnam

Virtual assets constitute a broad category, and various types have emerged in Vietnam. These include internet domain names, email, and most notably virtual assets within online gaming and even virtual currency like Bitcoin, etc. With the development of Blockchain technology, most types of virtual assets and virtual currencies are commonly used as traditional assets, with Bitcoin being the most prominent. In the form of virtual currencies, Bitcoin emerged and made a significant impact on the virtual community in Vietnam since 2013. Upon its introduction, legal framework concerns about Bitcoin were raised by the State Bank due to its non-acceptance as a legal currency or payment method in our country. However, despite these warnings, Bitcoin is still owned by Vietnamese individuals, constituting up to 31% (and at times reaching 40%) of the total virtual currency ownership.

In addition to Bitcoin, a multitude of other cryptocurrencies have also emerged in Vietnam, such as Ethereum (ETH), Binance Coin (BNB), RIPPLE (XRP), Tether (USDT), Cardano (ADA), Polkadot (DOT), Dogecoin (DOGE), Uniswap (UNI), etc.

“Bitcoin Robbery” and Its Legal Validity Question

In May 2023, the People’s Court in Ho Chi Minh City adjudicated a criminal case related to the robbery of virtual currencies. Specifically, the offenders staged a traffic accident, seized control, and demanded the victim to disclose their phone password to access the personal electronic wallet. Then, they transferred various virtual currencies to the offender’s wallet, totaling a value of up to 37 billion Vietnamese Dong.

A noteworthy aspect of this case is that the Trial Council opposed the defense lawyer’s argument, contending that Bitcoin is not legally recognized in Vietnam, therefore, misappropriating Bitcoin does not constitute the crime of “Robbery”. Nevertheless, the Trial Council asserted that although Vietnamese law has not accepted Bitcoin as currency or a means of payment, the act of robbing Bitcoin constitutes an offense. In reality, the accused had planned and executed the robbery of Bitcoin, subsequently selling it and benefiting from the proceeds, thus fulfilling the elements of criminal offense.

Within the scope of this article, the authors shall not discuss the accuracy of applying indirect valuation/exchange rate methods but solely focus on the legal aspects of Bitcoin. It is evident that, from the perspective of the Trial Council, while Bitcoin is not recognized as a currency, assessing its value in terms of money – a type of property, is easily accomplished by appraising agency. This implies that the economic value held by those who own it cannot be denied. From a theoretical perspective, “robbery” is a crime with formal components, meaning it constitutes a crime with objective signs of being a dangerous behavior for society. From their behavior, the accused were fully aware that using force and threats to control the victim, and subsequently seizing Bitcoin constituted behavior detrimental to society. In essence, the accused committed acts aimed at misappropriating Bitcoin, and subjectively, they perceived this virtual currency as property (as the accused sold Bitcoin to convert it into Vietnamese Dong and used it collectively). Therefore, the perspective of the Trial Council is entirely justified and reasonable.

Currently, many debates persist, arguing that determining the act of robbing Bitcoin as constituting the crime of robbery implicitly acknowledges virtual currency as property in Vietnam. Despite the controversies, it is evident that state agencies, especially law enforcement agencies, have taken initial steps in refining the legal framework for various forms of virtual assets. This aims to regulate and protect the legal rights and interests of citizens, preventing illegal activities related to this form of virtual assets. But in general, the inquiry into the legality of Bitcoin remains unresolved and necessitates anticipation of further actions from the relevant authorities.

Recommendations on Recognition of Virtual Assets in Vietnam

For conformity with the remarkable advancements in international law, it is necessary to recognize the legal validity of identifying virtual assets in Vietnam. This is because, fundamentally, virtual assets share similarities with property rights that are held in monetary value, transferred in civil transactions, and governed by individuals.

In essence, virtual assets are merely representations of information existing in the form of specific computer code. Therefore, they exhibit a unity of intrinsic and outward characteristics, similar to conventional assets. However, since computer code does not exist independently, ownership rights cannot be directly exercised, and these rights can only be realized through the monetary value of the virtual assets. This nature is not dissimilar to intellectual property rights (intangible in nature) recognized as a property right in Vietnam.

Additionally, virtual assets are also the result of human intellect and labor, serving specific human needs and could be recognized for their value within the user community as other traditional assets. This intangible form of property, not accessible in a physical sense, is authenticated through encryption using distributed ledger technology, characterized by decentralization, and governed by consensus principles.

With the on-going argument circulating about the recognition of virtual assets, many questions remain unanswered, leading to the fact that policymakers will put in more effort in order to put virtual assets under the governance of law. Pending their further actions, several recommendations are offered to provide a legitimate legal framework and prevent potential risks on the ground. In particular, the remarkable points such as:

- Firstly, virtual assets have experienced significant growth, leading to their falling outside the control of state authorities. Therefore, state agencies need to take initial steps to review and assess the current state of these assets in Vietnam. This is to identify their responsibilities and establish suitable mechanisms for control and risk mitigation.

- Continuing with the analysis, virtual assets are not legally recognized in Vietnam. Disputes arising from them also fall outside the scope of Vietnamese law regulation. Therefore, to ensure a complete legal framework, the SBV needs to collaborate with specialized agencies to establish regulations on the definition, nature, identification methods, legal validity, etc. to recognize virtual assets and transactions related to virtual assets.

- Thirdly, due to the intangible nature of virtual assets, entities engaging in related transactions may not be aware of potential risks, such as the misuse of virtual currency for fraud, money laundering, tax evasion, etc. Therefore, state authorities must establish special control mechanisms by categorizing the virtual asset business sector as conditional business lines, allowing operations only with the issuance of licenses.

It is important to understand that investors will bear all the risks when participating in virtual asset investment activities as they are not legally protected. While virtual assets may offer substantial benefits, the potential risks and losses could be significantly greater. Therefore, the authors recommend that one should either refrain from or exercise caution when engaging in transactions, buying, selling, or exchanging related to virtual assets in any form to avoid “money wasted, illness gotten”.

Conclusion

The Vietnamese government is taking steps to establish a legal framework for virtual assets, which will help dismantle initial legal barriers and facilitate the development of this asset class. However, it is important to note that virtual assets come with various risks, and it is crucial to manage and regulate them effectively to prevent potential challenges.